The Nature of Distributed Systems

- Intro

Content

The Internet evolves rapidly. We started our own hardware servers, moved to managed hostings and now we have entered the era of cloud computing. The ever growing need to handle more and more traffic pushes us beyond the limits.

As a result, it’s so natural nowadays to spin off a few instances on AWS or GCP and start building one’s own SaaS service that will scale in a way we need. Perhaps, your infrastructure already has load balancing, a couple of nodes or a message queue which means you have already begun with building a distributed system.

But what do we even know about distributed systems? Are they really different to simple single server setup?

Despite all benefits, I feel like many people underestimate challenges that come out of the box with distributed setups. So our goal is to dig into the nature of distributed systems and improve our reasoning about them.

Single Server Setup

The Single server setup is when your application, database and files are served on the same physical or virtual server. It is a reasonable baseline and often you may never need more than that. We work a lot with this kind of system. Even our personal computers may be an example of the single-node systems.

This is probably how we can get in a situation when we tend to apply our single server mental model to think about distributed systems. However, distributed setup is a fundamentally different beast and it has four main differences:

- Latency - when we have a single server, it’s CPU power and latency we worry about. In distributed systems, our main concern is network latency.

- Memory Access - in a single server, we have access to the same memory space, so it may be easier to write programs that interact with each other. You cannot get direct access from one server to another.

- Partial Failures - both distributed and a single node systems have components that could fail. In the case of a single server, there may be either total failure of the server (OS crashes or failures on the ISP side) or partial failures of the applications installed on the server. Every single component in a distributed setup surely shares these problems. However, they become undisguisable from each other. Having more components only increases the chance that some of them would be affected by some failures.

These few differences are so significant that they effectively change the way we need to think and build distributed systems.

Beyond Single Server

From the brief comparison it becomes clear that the role of the network is crucial in multi-server setups. In order to let services communicate with each other, they expose accessible APIs via standard protocols like:

- REST

- SOAP

- RPC

This helps to overcome memory access limitations. Communication itself happens via network links and this is where the fun part starts.

Unreliable Network

The role of the network becomes significant in the distributed systems. The problem is that the network is not a reliable thing.

Requests over the network can fail and there are a lot of reasons for that. Your router may just stop working because of a software or hardware issue, your load balances may drop some requests your database cluster silently or maybe someone just wants to cut your connection cable. Wild nature doesn’t help you either.

In other cases, your hardware may be partially faulty in a way that would slow down the whole nodes that it connects. So troubleshooting becomes time-consuming and painful.

While people work on making networks reliable, there will probably always be a reason that causes the failure.

Even if network links work well, it doesn’t mean that we are safe.

Network can be intercepted and the information may be recorded, modified or fabricated. This becomes an issue if transmitted information is confidential like PII or CC data.

Two Generals

Work in an unreliable environment is a common problem of all distributed systems. It’s being generally formulated as Byzantine General’s Problem.

Imagine there are a few armies with generals that besieged the city they want to capture. In order to successfully perform the campaign, they need to attack the city at the same time. Otherwise, their resources would not be enough and the city army would defeat them.

The only way generals can communicate is via messengers that have to bypass the enemy territory to deliver a message to another general.

The situation is complicated as messengers can be intercepted and the message can be fabricated. Also, both messengers and generals can be traitors that are the objective to fail the operation and save the city.

Generals and messengers need to agree on all messages that they send to each other in order to win the battle. This agreement is called consensus.

In a context of distributed systems, the consensus is important to synchronize the state of the system when it’s distributed among several nodes.

Latency, Bandwidth and Transport Cost

When two applications communicate on the same server, the communication latency is super small and close to zero. In contrast, communication over the network is a different story.

Network latency can be a few orders of magnitude higher than communication inside of the same memory space. Two computers from different parts of the world are connected via optical cables and the light is used to transmit information. So we seem to be pretty much limited to the speed of the light at this point. All of this tells us that latency is a new and important factor in distributed systems.

Another resource associated with communication over the network is bandwidth. Each network connection has a bandwidth limit and you cannot send a larger chunk of data over a unit of time via the network. This is especially important when you deal with file uploading and downloading like in Google Drive, Dropbox or even Netflix where you need to stream high-quality video files for millions of users over the globe.

Latency and bandwidth are two main costs of information transportation. However, there are other ones. For example, you will definitely pay for the whole network infrastructure needed to make your communication possible. Even if that cost is hidden in the cloud provider tariffs.

Yet another cost is the CPU resource you spend on serializing and deserializing data as well as the cost of TCP and HTTPS handshakes. This is the cost we need to pay in order to transfer data between transportation to application layers. The same story goes for when we decide to compress and decompress data in order to speed up data transmission and optimize bandwidth.

In order to imagine all of this, let’s take a look at some measurements that were done in Google data centers a while ago. They still are useful when you compare them:

- Main memory reference - 100ns

- Compress 1KB with Zippy - 10,000ns (10 us)

- Read 1 MB sequentially from memory - 250,000ns (250us)

- Round trip within the same datacenter - 500,000ns (500 us)

- Read 1 MB sequentially from 1 Gbps network - 10,000,000ns (10,000 us or 10 ms)

- Read 1 MB sequentially from HDD - 30,000,000ns (30,000us or 30 ms)

- Send packet CA -> Netherlands -> CA - 150,000,000ns (150,000us or 150ms)

This may be counterintuitive, but in some cases, network communication may be faster than reading from disk. Above we see that reading 1MB of data is a few times faster from 1Gbps network than from HDD.

CAP Theorem

Network hardware and software are not the only unreliable components. We can easily imagine a situation when some of the connected nodes become faulty because of a broken hard drive or RAM stick. In such cases, there is a part of the distributed system that still works and another part that is failed. These situations are just inevitable.

What can we do about it? We need to manage such failures and build system architectures around this fundamental problem. Such systems are called fault-tolerant.

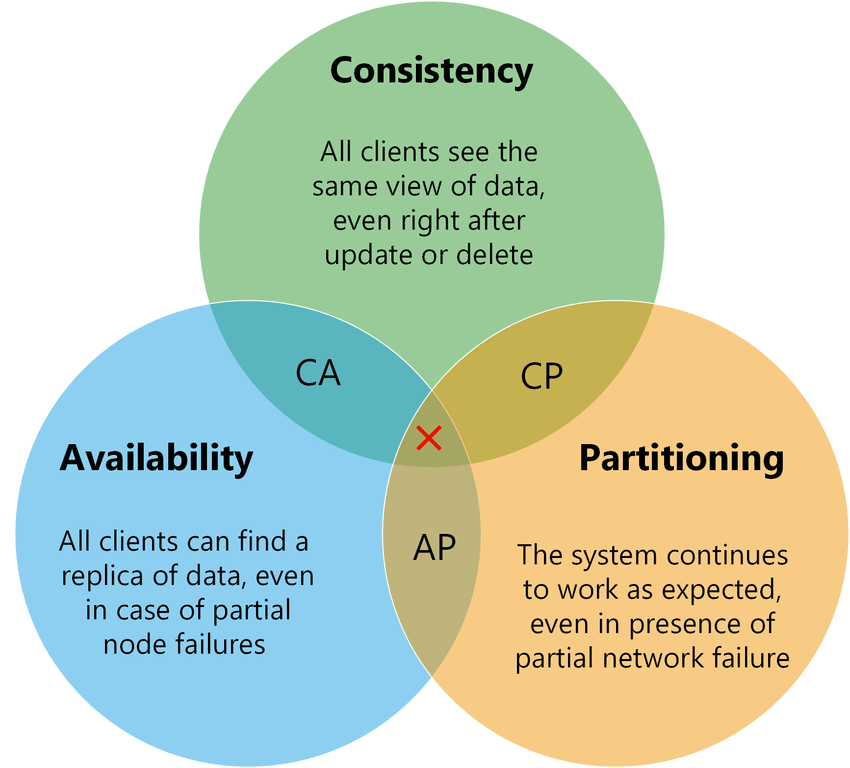

CAP theorem says that there are two logical ways to respond to the partial failure of the system:

- keep part of the system outdated but available for other clients

- lock the system until all nodes become consistent after the failure

The most important is that we cannot pick all three of these attributes: Consistency, Availability and Partial Failure Tolerance.

Another interesting thing is the Consistency-Availability pair. Since partial failures are unavoidable, it’s effectively not possible to implement this pair for distributed systems and it should be only possible in the case of a single-server setup.

However, failures don’t happen all the time and most of the time the system is in a fully functional state. That’s why there is an addition to the CAP theorem called the PACELC theorem.

PACELC theorem states that when there are no partial failures in the system, then a distributed system can trade between latency and consistency. In other words, in case you have a horizontally scaled cluster with a couple of nodes, then you can balance your system latency over consistency by choosing the number of nodes you need to have in sync when change happens. The change may be propagated with a few nodes right away and respond to the client after that. The rest of the nodes eventually become synced with this change over time. On the flip side, you can wait until all nodes get in sync and only then respond to the client. In the second case, we get a strongly consistent system, but with a higher latency comparing to the first case.

By choosing the number of nodes we want to have in sync when changes happen, we can specify the level of consistency of the system.

At Least Once Delivery

Yet another interesting implication of partial failures is that it’s hard to deliver messages exactly once every time.

When a client dispatches a message it transmits to the receiver, the receiver persists the message and respond by an acknowledge message back. This is a normal flow.

Let’s make it real by adding a partial failure. Now when the client sends a message and doesn’t get a response in a reasonable amount of time. Maybe the receiver is down? Or there was a network failure? Or maybe the receiver is just overloaded at this time and slow down with response?

There is no way to distinguish these issues. The message we try to send may be really important like an order fulfilment request. We are better to be safe than sorry. So the client sends out one more message and waits again. We do this until we are sure that the message is received e.g. when we receive an ack message in response.

However, at that point, the receiver may get several duplicated messages.

For this reason, we need to make sure that message workers have business logic that would not make the system state inconsistent in case of message duplications (e.g. customer is being charged a few times for the same order). Sometimes this property is called idempotency.

Summary

I hope you noticed that designing distributed systems is a good fit for pessimists, because you always need to expect that system could partially fail at some point.

Other than that, distributed systems have inherited complexity associated with their distributed nature. That’s why you need to go building such a system if they are absolutely needed.

The distributed world is all about tradeoffs. You need to know and realize them to successfully build robust distributed systems.